Reading is a fundamental skill, and getting it right in the early years can make all the difference to a child’s future success. Because early reading is so important to get right, many educators are turning to the Science of Reading to inform the structure and content of their reading instructional practices.

The Science of Reading, as defined by the Reading League in 2022, “is a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing. This research has been conducted over the last five decades across the world, and it is derived from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages.” Reading research suggests that 95% of students can learn to read with instruction and programs based on the Science of Reading — compared to just 30% without it.

However, there are some common misconceptions about the Science of Reading that can hinder its effective implementation. We spoke to CORE Educational Services Specialist Kristina Jaramillo about the ten things teachers need to know about the Science of Reading. Here’s what she had to say.

10 Things Teachers Should Know About the Science of Reading

1. The Science of Reading Is Not a Fad

Teaching trends may come and go as the decades pass, but the Science of Reading, based on over 50 years of research in multiple fields, provides the evidence as to what works in literacy instruction and what does not.

Therefore, it is not a fad or trend but a verified way to help students of all backgrounds, levels, and abilities learn to read. The Science of Reading demystifies the process of learning to read and provides specific tools and methodologies to help teachers teach reading effectively.

2. All Kids Benefit from The Science of Reading

Although reading has traditionally been taught in many different ways, you might be surprised to learn that all children learn to read the same way. This is because reading isn’t a skill that develops naturally — we all have to build the neural pathways in our brains that allow us to read through “explicit instruction and deliberate practice,” according to Kristina.

She explains that some teachers think phonics instruction isn’t necessary, but they’re referring to the roughly 40% of children who learn to read regardless of whether it’s taught badly or well. The other 60% need explicit instruction to learn how to read, and even the 40% of children who learn to read easily benefit from explicit instruction to help them learn to spell and break down longer words.

Kristina recommends that teachers watch this video by Stanislas Dehaene to understand how children learn to read.

3. It’s Okay to Have Made Mistakes

If you realize you’ve been using ineffective approaches to teaching in the past, don’t worry. Kristina shares that at the beginning of her career, she was trained as a Whole Language teacher, but when she began teaching, she quickly realized that she didn’t know how to teach children to read.

While it’s okay to have made mistakes in the past, it’s not okay to keep teaching using ineffective practices once you know better. Implementing Science of Reading practices may look different from what you’re used to, so Kristina recommends keeping an open heart and mind.

4. Teaching Reading Doesn’t Have to Be Complicated

Teachers love incorporating new fancy tools and methodologies into their teaching practices, but the reality is they don’t need bells and whistles and pretty stuff to teach students effectively.

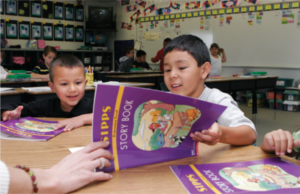

Students can learn to read very effectively with just a few simple tools — such as letter/sound cards, dry-erase boards and markers, and decodable text (texts where they apply their phonic skills in reading actual text).

Students also do not need worksheets, computer programs, or Pinterest activities to learn how to read. They need a high-quality curriculum, opportunities to practice word reading in connected text, and teacher-led opportunities to develop reading comprehension strategies in high-quality complex text.

5. There Is No Magic Bullet

Teaching reading effectively is a combination of teacher knowledge, good assessments, high-quality materials, explicit instruction, and lots of opportunities for students to practice reading.

Understanding the Science of Reading and implementing it effectively are not the same. There is no perfect reading program, and teacher knowledge is the key to implementing programs effectively.

6. The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Kristina wishes that all teachers knew about the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Rope. The Simple View of Reading explains that comprehension requires both word recognition and language comprehension — it’s not an either-or.

Scarborough’s Rope takes the analysis even further by looking at the components that make up word recognition (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency) and the components that build language recognition (such as background knowledge, vocabulary, use of metaphors and similes, print awareness, and understanding genre).

There’s so much more to teaching reading than phonics — you’re building word recognition and language comprehension simultaneously, which are the two sides of the rope.

If you teach young children who don’t yet have word recognition, you can build their background knowledge and vocabulary through diverse content-rich read-alouds while students are still learning how to decode. They don’t need to be able to decode to build background knowledge and vocabulary.

7. The Science of Reading Applies to All Students

Because our brains all learn to read the same way, the Science of Reading works for all students — including ones with dyslexia or other reading difficulties and learners with linguistic differences. All students benefit from systematic and explicit reading instruction that includes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

If a child is learning to decode and they don’t have the language skills they need to understand what they’re decoding (for example, in the case of English language learners), by the time they develop the necessary language skills, they will already have the ability to decode. Therefore, it’s essential to teach decoding skills to all students so they don’t fall behind later on.

8. Teachers Need Training to Implement the Science of Reading

Sometimes, strategies such as Sound Walls or Heart Words start trending on social media, and teachers think that if they implement one of these things, they are implementing the Science of Reading.

This approach is not the right way to teach the Science of Reading. Teachers need to have a solid understanding of the Science of Reading to be able to implement these tools effectively and in the right contexts. “Just changing a couple of things in your classroom is not going to have the impact you think it’s going to,” Kristina says.

9. Feelings Do not Equate to Evidence

Teachers will often rely on their instincts rather than data to determine the effectiveness of their instruction, but it’s essential to look at the data to see the real impact of your work.

If you think your instruction methods are effective, ask yourself — which students are learning? Is it the 40% that would have learned anyway, regardless of the instructional methods used? Are you in an affluent community where the kids who don’t learn to read have access to private tutors?

A data-based approach to teaching requires valid and reliable assessment tools. Teachers need to look at the data and make changes in their instruction based on what it tells them, including targeted interventions where needed.

The bottom line? Base your assessments on data, not feelings.

10. Literacy Instruction Is a Civil Rights Issue

Teachers have a huge influence on their students’ outcomes later in life. The choices you make about how to teach reading will determine which college they go to and what careers they pursue.

All students deserve evidence-based instruction, and teachers need to make sure they give students the tools to participate in grade-level reading and thinking.

The Science of Reading 5 Core Skills

The National Reading Panel (NRP) Report in 2000 identified the following five elements as the most important foundational skills students need to become proficient readers.

1. Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is recognizing that words are composed of individual sounds that can be blended together for reading and pulled apart or segmented for spelling.

2. Phonics

Phonics is a method of teaching students how to connect the graphemes (letters) with the phonemes (sounds) and how to use this letter/sound relationship to read and spell words.

3. Fluency

Reading fluency is reading text with sufficient speed and accuracy to support comprehension. The practice of developing fluency in children includes reading accuracy, reading rate, and reading expression. Instruction in reading fluency should include assisting students in developing their ability to use typical speech patterns and appropriate intonation while reading aloud.

4. Vocabulary

Vocabulary is the understanding of individual word meanings in a text. Teachers should develop students’ vocabulary knowledge through direct and indirect methods of teaching, and students should be exposed to vocabulary both orally and through reading.

5. Comprehension

Comprehension is the understanding of connected text and is the ultimate goal of reading.

Help Your Students Develop the Reading Skills They Need

The Science of Reading is a powerful, effective approach to teaching reading based on a large, interdisciplinary body of research developed over half a century. Incorporating it into your teaching practice can help all students develop the literacy skills they need to succeed in life.

If you want to develop or deepen your knowledge of the Science of Reading, you may be interested in CORE’s Online Elementary Reading Academy. This seven-week course will provide you with the skills and resources to deliver standards-aligned and evidence-based reading instruction based on the Science of Reading.

The post 10 Things Teachers Should Know About the Science of Reading appeared first on Teacher Professional Learning | Literacy, Math | MTSS.

In August, CORE Learning convened the inaugural meeting of our newly formed CORE Math Advisory Board, a group of teachers, instructional leaders, and researchers with expertise spanning math instruction, assessment, teacher education, and professional learning. This advisory board

In August, CORE Learning convened the inaugural meeting of our newly formed CORE Math Advisory Board, a group of teachers, instructional leaders, and researchers with expertise spanning math instruction, assessment, teacher education, and professional learning. This advisory board

Professional learning and job-embedded coaching on how to deliver explicit reading instruction are essential to improving literacy outcomes for all students. But just as critical is the use of high-quality, evidence-based reading curricula, particularly when supporting striving readers at all grade levels. In a time when

Professional learning and job-embedded coaching on how to deliver explicit reading instruction are essential to improving literacy outcomes for all students. But just as critical is the use of high-quality, evidence-based reading curricula, particularly when supporting striving readers at all grade levels. In a time when